The mesmerizing world of Macropinna microstoma, particularly the members of the Opisthoproctidae family, unveils a spectacle rarely witnesse, a fish adorned with a transparent head. Although documented since 1939, the initial encounters with this extraordinary creature were marred by the intrusion of nets or lines, which punctured and deflated the distinctive fluid bubble that defines its uniqueness.

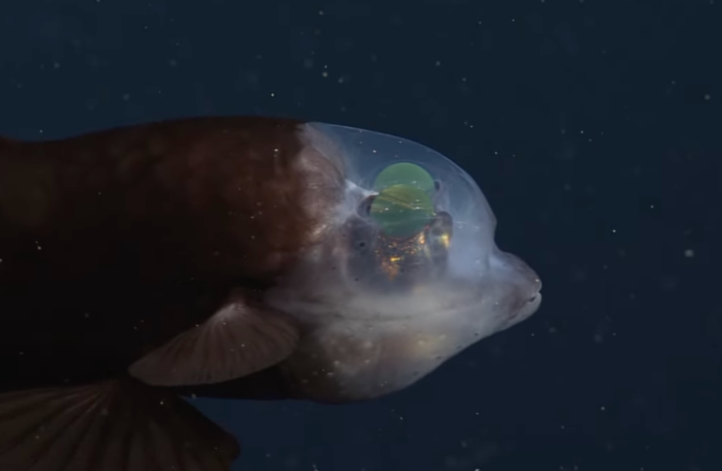

The transparent head of the barreleye serves as a cockpit of sorts, akin to a fighter plane. Remarkably, these fish can rotate their eyes backward and upward, granting them a comprehensive view of both prey and predators. A feat that not only proves useful but also distinguishes them as one of the few animals capable of showcasing their anatomy without succumbing to mortality.

Regrettably, these intriguing creatures inhabit the abyssal depths, preventing enthusiasts from showcasing them in household aquariums.

A recent breakthrough by researchers at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute unraveled a long-standing mystery surrounding the tubular-eyed, transparent-headed fish. Initially described in 1939, the barreleye fish Macropinna microstoma had perplexed marine biologists with its tubular eyes, renowned for their exceptional light-collecting abilities.

The prevailing belief was that these eyes remained fixed, providing only a limited “tunnel-vision” perspective of the space directly above the fish’s head. However, a groundbreaking paper by Bruce Robison and Kim Reisenbichler dispelled this notion, revealing that the unique eyes could rotate within a transparent shield covering the fish’s head. This newfound ability allows the barreleye to gaze upward at potential prey or focus forward to observe its meal.

The barreleye, scientifically known as Macropinna microstoma, possesses highly light-sensitive eyes enclosed within a transparent, fluid-filled shield. Capped by vibrant green lenses, the tubular eyes point upward when the fish seeks food overhead and forward when engaged in feeding. Notably, the fish’s olfactory organs, called nares, akin to human nostrils, are positioned above its mouth.

Adapted to the lightless abyss, deep-sea fish in the Opisthoproctidae family, colloquially called “barreleyes”, employ various remarkable strategies. Their tubular eyes, while adept at collecting light, suffer from a limited field of view.

Until recently, scientists believed these eyes to be immobile, restricting the fish’s vision to what lay directly above. Bruce Robison and Kim Reisenbichler’s investigation, utilizing video footage from MBARI’s remotely operated vehicles, unveiled a transparent, fluid-filled shield surrounding the fish’s head, a feature often overlooked due to its fragile nature, frequently damaged during the ascent from the depths in nets.

The stroke of fortune allowed the researchers to bring a net-caught barreleye to the surface alive, confirming through controlled observation that the fish could rotate its tubular eyes as it shifted from a horizontal to a vertical position.

Beyond their captivating headgear, barreleyes exhibit an array of adaptations for deep-sea life, including large, flat fins for precise maneuvering and a small mouth for selective prey capture. However, their extensive digestive systems suggest a diet encompassing various drifting animals and jellyfish fragments found in the stomachs of net-caught specimens.

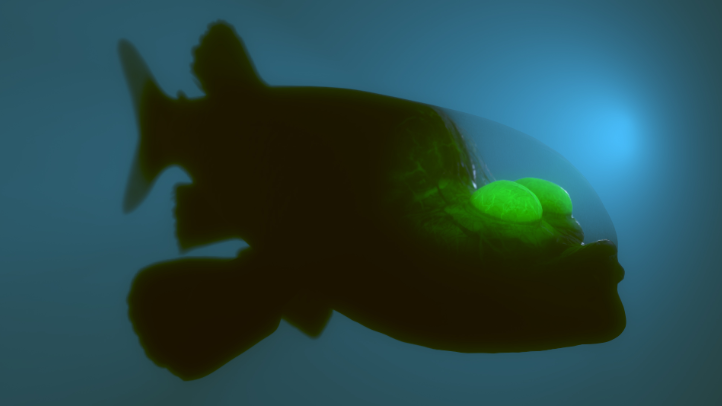

After meticulous documentation and analysis of the barreleye’s unique adaptations, Robison and Reisenbichler proposed a working hypothesis regarding the fish’s behavior. Typically motionless in a horizontal position with eyes gazing upward, the fish uses its green-pigmented eyes to filter out direct sunlight, facilitating the detection of the bioluminescent glow of overhead jellies.

When prey is spotted, such as a drifting jellyfish, the fish rotates its eyes forward, transitioning into feeding mode by swimming upward.

Sharing the deep-sea realm with diverse jellyfish species, barreleyes, it is speculated, navigate adeptly among the tentacles of siphonophores, such as those in the genus Apolemia. These siphonophores, resembling living drift nets, trail stinging tentacles that capture copepods and other small organisms.

The barreleye’s rotating eyes and transparent shield serve as strategic assets, enabling the fish to navigate through the tentacles while safeguarding its eyes from the stinging cells of the siphonophore.

Source: MBARI